The title may be a little inflated but what I would like to cover in this article is what I believe to be the single most important strategy point for Verbal questions and one that cuts across all Verbal questions types on both the GMAT and GRE. It is what I call “The Principle of No Ambiguity.”

Most people understand that Quant questions are completely unambiguous: there is only one right answer and all of the other answers are necessarily wrong. Math is obviously very black and white in that way; if the answer is 4, the answer cannot also be 5 or 7. That’s just the way Math is. Most people, however, fail to realize that Verbal questions are the same way, at least as far as standardized tests are concerned: they are completely unambiguous. It would not be fair if there were two theoretically correct answers on a GMAT or GRE question. And barring a really bad, poorly written question (which I would argue appears around 1 out of every 500 questions or so) it just won’t happen on the exams.

What most test takers do on GMAT or GRE Verbal questions is pick the answer that they think is “best.” This, however, is not the right way to think about Verbal questions. “Best” implies that there are other answers that would be acceptable and that the correct answer might just be a little bit better than one of the other answers. Again, this cannot happen on a standardized test, since it would lead to different answers being correct based on different people’s subjective assessment of what is “better.” The truth is that on all Verbal questions there will be 1 objectively right answer and 4 demonstrably wrong answers. And when I use the word demonstrably here, I mean it literally – one could demonstrate why each wrong answer is wrong.

Let me explain some of the ways in which this understanding can really affect ones Verbal performance (I would argue that it is the single most important strategy point to be aware of). As I have explained in other posts, hard questions are hard because most people get them wrong. So how do the writers of the test ensure that most people will get certain Verbal questions wrong? Well, they make sure that the correct answer doesn’t sound that good – they won’t make it wrong, of course, but it will be “acceptable” and will probably not sound like what most people would think the right answer should sound like. Further, they will make the wrong answers, or at least one of them, sound very, very good. That is why just picking the “best” answer or the “better” answer will often lead you astray on hard questions. The wrong answer probably will sound better than the right answer, but there will be something about it that just makes it actually wrong. The right answer might just be the answer that is simply “not wrong.”

Another important point here is how understanding this “Principle of No Ambiguity” can actually help you to get more answers correct. And this doesn’t even have to do with knowing more of the content – it is simply something that can push you to a deeper level of analysis and allow you to arrive at an answer with certainty rather than make what would amount to a guess (when you are choosing an answer that you think is “better” that is exactly what you are doing).

Essentially, when you are answering a question and find yourself in a position of ambiguity (i.e., you believe that 2 of the answers you are looking at could both be correct) you need to push yourself one step further to try to eliminate that ambiguity and understand why one of those answers must be right and the other one wrong (or, perhaps, why they are both wrong).

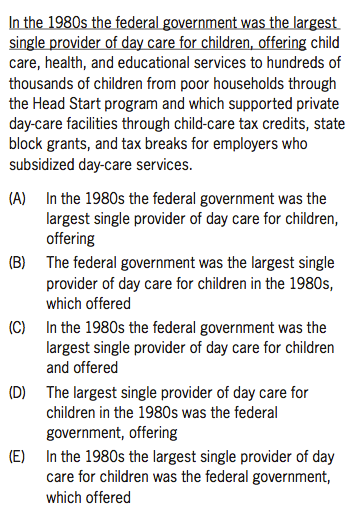

This principle is applicable to all Verbal question types that appear on the tests! However, especially for the purposes of an article like this, it is easiest to demonstrate the principle through GMAT Sentence Correction questions, which were a staple of the GMAT for decades before being removed in 2024. Consider the following:

Most people that I do this question with get it down to A and E (although some don’t even end up picking either of those). At that point, most people basically just guess and pick the one that “sounds better,” thinking that this is just the way it is on Sentence Correction questions (most people think choice A sounds better and pick that answer choice). But such thinking is a misunderstanding of the question type and of all Verbal question types on the GMAT and GRE. It would be completely unfair if choices A and E were both acceptable answer choices and if it were left to test takers to choose the one that they, in their subjective opinion, thought was better. There must be one and only one correct answer and the other answers must be demonstrably wrong.

So on the above question if you got it down to choices A and E and then got stuck there (or even if you thought that other answers could be correct as well), it means that you are missing something and that you need to dig deeper both logically and analytically. You either need to look more closely at the answer choices to try to spot differences or you need to consider the non-underlined part of the sentence. But there MUST be something that would make one answer correct and the other incorrect – again it is black and white!

In the above case, most people never glance back at the non-underlined part of the sentence, but in order to confidently answer this particular question correctly you MUST look there because it is there that the clue resides that would allow you to eliminate the wrong answers. Specifically, the “and which” that appears about midway through the sentence makes no logical sense unless there is a which that precedes it. It is really a parallel structure question, but most people never spot the clue that would allow them to see that. The correct answer is E: “….the federal government, which offered x…and which supported y…”

One could argue that this is an example of a straight up grammar issue and that a person who gets this wrong just doesn’t know their parallel structure rules. That is perhaps partly true, but I have found that the bigger problem is that most people just think that completing a Verbal questions is, by nature, an ambiguous exercise and that guessing is just part of the rules of the game. Of course one does sometimes need to guess, but if you realize that on every question there is only one acceptable answer and that the other answers are unacceptable for at least one reason (usually more), that alone may push you to be more analytical and more precise in the way that you approach Verbal question types.

I am not arguing that content (such as vocabulary knowledge on the GRE) does not play apart – it does. And I am also not saying that just reading this post will help all of your Verbal troubles melt away. I tutor people for many, many hours and sometimes it takes a while and a lot of practice just to really accept and be able to apply this one concept. But I would argue that it is THE starting point for being good at Verbal questions because it moves you away from the idea that Verbal questions are ambiguous and that you will never be able to arrive at answers with a very high degree of certainty. Verbal questions are really just like Math questions and the sooner you realize that the sooner you will start to unlock one of the keys to success on the Verbal section.