Most people take a rather informal, intuitive approach to verbal questions. This is often described as “using your ear”: simply reading the answer choices and trying them out in your mind’s ear, seeing which one sounds best. And here, dear reader, there lie dragons. Some of the test writers for the SAT, ACT, GMAT, and GRE are expert linguists whose job it is to turn the science of language against you; if you go up against their tricks unprepared, you’re in for a bad result.

On the one hand, using your ear is not a crazy thing to do. Humans are specially adapted for language, and it’s been observed that knowledge of our native language(s) is probably the most complex system of knowledge most humans will master in their lifetimes. We are experts in our language; why not use this ability?

Well, here’s the problem. There are a number of different factors that determine what “sounds right,” some of which you need to ignore for the purposes of the test. A successful approach is a deliberate and deliberative one, actively analyzing sentence structure, question type, answer choice design, and more.

Frequency is a False Friend on Verbal Questions

One factor influencing your judgment is implicit (or explicit) knowledge of the grammar rules of your language; another is your sense of what is and is not a reasonable way to complete the sentence to get an acceptable meaning. This is the kind of thing the test is designed to probe, and which you should be paying close attention to.

However, another factor that affects your judgment of what sounds right is how similar a sequence of words is to other sequences you’ve seen before. A number of language scientists work for the major testing companies, and they know how to exploit frequency of collocations (n-gram frequency, local statistical regularities) in order to trick you. The following GRE question, in which you need to select two words that give the sentence correct and equivalent meanings, illustrates this beautifully:

The correct answer choices are ideologues and zealots. However, a number of students mistakenly choose hypocrites and phonies. Why? On a quick reading, the meaning provided by hypocrites and phonies may seem appropriate enough. More importantly, though, hypocrites and phonies are just much more commonly encountered following the words “are complete,” as in “are complete phonies” or “are complete hypocrites.” Google search results for these strings provide a rough measure of their frequency of occurrence:

collocation –– collocation frequency

“are complete hypocrites” – about 8,650 results

“are complete phonies” – about 2,000 results

“are complete zealots” – about 129 results

“are complete ideologues” – about 95 results

If you’re simply “using your ear”, these first two will “sound right” just because they fulfill a prediction the text set up. They sound more like English; they are more likely to be encountered in this sequence as a matter of statistics (not grammar or meaning). Trusting this sense uncritically would lead you astray here, and on many other questions.

Now, it’s worth pointing out that knowing and exploiting the statistical properties of your language is a necessary skill in everyday life. We encounter language in noisy environments all the time, and we constantly have to guess at what we’ve heard and what’s coming next so that we can make sense of it all. But the crucial thing is that local likelihood is not the same thing as the “real” rules of language relevant to the test.

Long-distance Subject-Verb Agreement on the SAT and ACT

Another great case to illustrate this point is found in subject-verb agreement questions on the SAT Reading & Writing and ACT English sections.

“The sheer weight of all these figures make them harder to understand.”

Above, we have a real-life example of a subject-verb agreement error in the wild. Note the proper target of agreement (i.e., the noun in the subject that determines agreement properties, here “weight”) is abstract and singular, while the intervener (figures) is closer to the verb, and concrete and plural. These factors all make it harder to see that the correct verb form should be “makes”, not “make” (the way through is to identify the head noun “weight” and try it right next to the verb: “weight… makes” vs. “weight… make”).

The correct answer is (B), is. Note that the head-scratching choice offered between present and past is completely irrelevant (this is a common pattern).

Why is this question tricky? There are a number of factors that make this example particularly likely to trip up the unwary. One is the “distraction” regarding present and past tense that the test writers imbed in the question. But the trickiest aspect of this question is the fact that the local string “ears are” or “ears were” is much more English-like than “ears is”. Unless you are aware of this common trap and on guard, you are likely to miss it!

Leading You Down the Garden Path

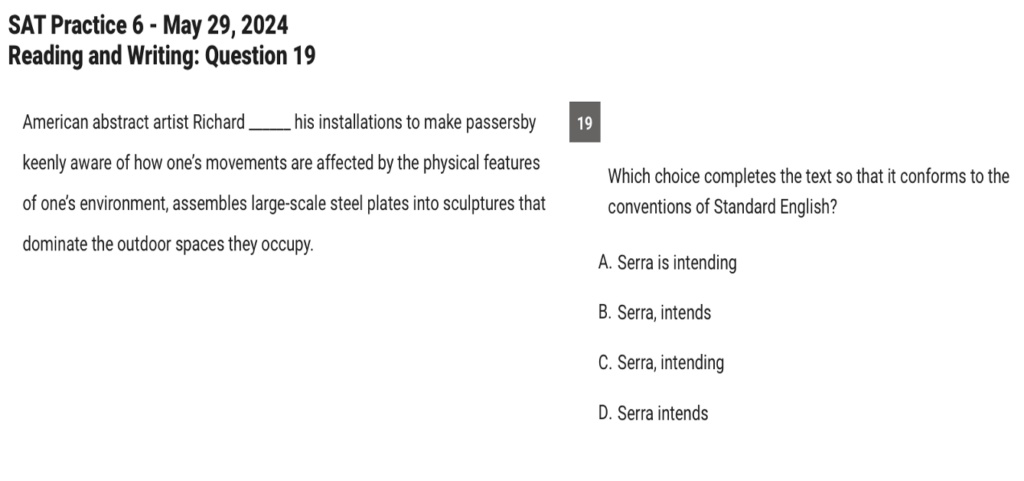

Here’s another example where we see predictions leading us astray, again from the SAT.

The correct answer is (C). The above sentence is (arguably) an example of what linguists call a garden-path effect. Statistical properties of English lead to an overwhelmingly strong prediction that the site after the subject (where the blank is) will be the location of the inflected main verb. It is only if students read far enough to encounter the word “assembles” – and then are able to reparse the sentence and discover the correct, more complicated structure in which “assembles” is the main inflected verb – that they can break out of this incorrect prediction.

Summary: Beware of Your Unexamined Intuitions!

We have seen several of the ways in which hard verbal questions are crafted to exploit how humans tend to make errors with language. In broad strokes, the way past these traps is to be more critical and introspective about your own judgments. It’s simply not good enough to pick the answer that “sounds best.” You’re looking for the right answer, and that’s not the same thing.

In fact, on the hardest questions, the right answer often doesn’t sound that good at all! You need to learn to ignore your sense of statistical likelihood, and practice deliberate techniques to identify and navigate the various traps that you will find laid before you.